Nowadays, theories cultivated by Cartesian dualism are becoming inadequate for understanding contemporary theatre and performing arts. Findings of cognitive science have brought major changes to our understanding of human brain and its mechanisms. These changes have shifted our assumptions about the body in its every aspect. Today we know that there is no “reason” and “meaning” independent of bodily capacities such as perception and movement. “Meaning” and also its creation are fully embodied processes. That is why there is an increasing tendency towards somatic practices in the field of theatre and performing arts, which can be seen as a consequence of these developments. This paper is focusing on the way, in which somatic practices can be used in educating theatre directors, and also, why this is of importance. The word “soma” means the body in its wholeness. “Somatics” refers to a manner of looking at oneself from the inside out, while being aware of feelings, movements, and intentions, rather than looking objectively from the outside in. Bodily movement offers an entirely new language of consciousness and body wisdom through self-awareness and self-guidance. Somatic studies cover different practices such as the Feldenkrais method, Laban/Bartenieff Fundamentals, Alexander Technique, Pilates etc. Each somatic practice approaches body-mind relations from a different perspective, yet there are some common goals in the education in somatic practices: emphasis on the process over a goal-oriented product by enhancing kinaesthetic awareness in a non-judgmental and non-competitive environment, use of sensory awareness and observation of interactions with space, time, and the others in order to become a good observer of one’s own also the others’ movement. This paper discusses those functions of somatic practices in the director training process in terms of triggering creativity and also building a new relationship with the audience and performers, as looking The Commedia School’s curriculum which is one of the oldest physical theatre schools based in Copenhagen.

Bilge Serdar Göksülük recently completed her PhD degree at Ankara University, Department of Theatre Theories, Criticism and Dramaturgy. Her research subject is “Soma” as a new body phenomenon in performing arts, and application of somatic practices on the stage. She received her master’s degree at the same department, having written a master’s thesis on The Place and Functions of Dance as an Aesthetic Experience in Theatre for Young Audience. She also studied physical theatre at the Commedia School in Copenhagen (Denmark) and Laban/Bartenieff Movement Studies in Berlin (Germany). Bilge Serdar has presented papers about her studies at international conventions and seminars. She had experienced giving lectures about movement and creative drama at Ankara University and has also held workshops for actors on “Reconstruction of Staging Body with Laban/Bartenieff Studies”. She is a board member of ASSITEJ Turkey (International Association of Theatre for Young Audience) and has been working as an organizing staff member of a number of national and international festivals, seminars, workshops, and artistic gatherings since 2008. She is, moreover, one of the co-founders of the Copenhagen based Theatre Lokus. She is currently continuing to do her research on both practical and theoretical level within Choreomundus – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice, and Heritage program.

Nowadays, theories cultivated by Cartesian dualism are getting inadequate to understand contemporary theatre and performing arts. Findings of cognitive science made major changes in our understandings of our brain and its mechanism. These changes shifted our assumptions about body in every aspect. Today we know that there is no “reason” and “meaning” independent of bodily capacities. That’s why there is an increasing tendency to use somatic practices in performing arts fields. In my research, I basically posit that somatic practices have a crucial role in theatre education and specifically in director training. I try to find convincing theoretical arguments and scientific results to support my suggestion, beside my own experience in physical theatre training in The Commedia School in Copenhagen and in Laban/Movement Studies in Berlin. In my paper, I’m going to make reference to main and common features of somatic practices. Then I’m going to mention The Commedia School’s training approach created by Ole Brekke as an example of somatic training in theatre education. Before starting to discuss my main argument, I want to begin with describing a notion of “contemporary director”.

New Tasks of Contemporary Director

It’s important to mark out tendencies in contemporary theatre practices to formulize my question of why somatic practices are important in director training. In her book Making Contemporary Theatre Jen Harvie ties together ongoing theatrical trends as “interrogation of the roles of text and director, devising collectively, self-reflexive attention to dynamics and ethics of creation process amongst all participating makers” (Harvie 2010: 2). Also, she shares some qualities of postdramatic theatre described by Lehmann: “more presence than presentation, more shared than communicated experience, more process than the product, more manifestation than signification, more energetic impulse than information” (Lehmann 2006: 85). These quotes from Lehmann and Harvie highlight the importance of rehearsal as a creation process and undermine the explicit supremacy of the text and also the director. That is because the characteristic of the aesthetic aspect of the performance is not predetermined by the text or director, it is implicit in the quality of the creation process which is required participation of all agencies. As Pavis indicates “the director no longer needs to be preoccupied with knowing what is underneath” (Pavis 2013: 284).

The actor’s position has also shifted in contemporary practices. Lehmann indicates that before modernism actor’s body was disciplined, trained and formed to serve as a signifier; but it was not an autonomous problem and theme of the dramatic theatre, but modernist theatre and postdramatic theatre gain new potentials from overcoming the semantic body (Lehmann 2006: 162). Then what we want from the actor is, as Lehmann states, to offer himself, not just to present something or somebody, but to “presence” on the stage. Actor’s individuality becomes more important than the character in the creation process. So, as Pavis implies, a search for authenticity and psychological precision become important for many directors (Lehmann 2006: 284). Lehmann cites from Valère Novarina, “the actor is no interpreter because the body is no instrument” (Lehmann 2006: 163); then the director should be able to canalize/guide actor as a creator. What is expected from a new director is to facilitate these collaborative processes and to “decenter the actor” to trigger creativity and make her a full partner of director. As Pavis indicates, then actor becomes a double who is “preoccupied” not with the self anymore, but with the overall functioning of the scene (Pavis 2013: 284). In my paper I will also follow this notion of director: “director as facilitator” (Harvie 2010: 12).

I also want to mention the concept of “embodiment” in contemporary theatre. While the position of the body has been changing in performing arts with different reasons, “embodiment” has become an aesthetic argument in the field. For Erica Fischer-Lichte “by emphasizing the bodily being-in-the-world of humans, embodiment creates the possibility for the body to function as the object, subject, material, and source of symbolic construction, as well as the product of cultural inscriptions” (Fischer-Lichte 2008: 89). And she indicates that the concept of embodiment signifies a correctional shift in methodology away from concepts such as “text” or “representation”. That’s why “the concept of embodiment becomes one of the key importance to aesthetics of the performative” (Fischer-Lichte 2008: 90). Here the vital point is the link between embodied philosophies and somatic studies, but before that it’s important to begin with the description of somatic field.

What is Somatic Approach?

It’s important to start with clarification of what is meant by somatic practices, somatics or somatic approach. It’s known that the origins of western somatic education are rooted in a philosophical revolt against Cartesian dualism. The word soma means “the living body in its wholeness” in Greek (Hanna 1980: 6). In the 70s Hanna for the first time coined the term “somatics” to describe a field of study that is interested in an embodied process of internal awareness and communication and also focuses on an inner experience (cf. Green 2002). According to Hanna, what is meant by soma and body is different. “Soma is not a thing or an objective body, but rather is a process. Also, soma is neither static nor solid; it is changeable and supple and is constantly adapting to its environment” (Hanna 1980: 6). So far Hanna’s descriptions promise a new relationship with/within our body and also with our environment which we are looking for in the field of contemporary theatre.

When we talk about somatic practices, we mean different modalities such as Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement, Laban/Bartenieff Movement Studies and so on. All these modalities have different approaches: for example, “Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement makes use of exploring slow movements with ease in order to help students find more efficient movement patterns, Bartenieff Fundamentals explore movement initiation and intent” (cf. Green 2002) or Laban Movement Analyses focus on bounds between inner functionality and outer expressiveness. Although all these practices have different focuses, they have some common goals. Also, The International Somatic Movement Education and Therapy Association (ISMETA) describes the common goals of somatic movements to provoke participants to:

– focus on the body both as an objective physical process and as a subjective process of lived consciousness;

– refine perceptual, kinesthetic, proprioceptive, and interoceptive sensitivity that supports homeostasis, co-regulation, and neuroplasticity;

– recognize habitual patterns of perceptual, postural and movement interaction with the environment;

– improve movement coordination that supports structural, functional and expressive integration;

– experience an embodied sense of vitality and create both meaning for and enjoyment of life (ISMETA).

I assert that somatic training can lead Shusterman’s “somaesthetic” awareness which is defined as “the critical, meliorative study of the experience and use of one’s body as a locus of sensory-aesthetic appreciation (aesthesis) and creative self-fashioning” (Shusterman 2008: 1). This perspective gives the body’s inner experience the credit back. Of course, all these things are much more complicated process than the assumption, but we have valid proofs to believe that our own body images and bodily connections affect our thoughts, feelings, emotions and “self” since making meaning process rooted in our body and in our movement (see Mark Johnson, Antonio Damasio, George Lakoff, Mark Turner and others). For my argument it is important to understand the bodily basis of meaning, thoughts and feelings before continuing.

Embodied Philosophies and Some Scientific Proofs for Somatic Trainings

Embodied philosophies and theories supported by empirical researches of cognitive science provide us a holistic approach about meaning, thought, feelings, emotions and imagination. Johnson states that “embodied view of mind sees meaning and all our higher functioning as growing out of and shaped by our abilities to perceive things, manipulate objects, move our bodies in space and evaluate our situation” (Johnson 2007: 11). Here are some implications of embodied philosophies important for my claim stated by Mark Johnson in his book The Meaning of the Body:

This holistic approach about mind and body is compatible with somatic holistic perspective. Embodied approach makes the “bodily movement” one of the key elements. And this overlapping gives us a strong opinion about why we can think somatic practices are practically applications of embodied philosophies. Johnson in the very beginning of his book assume that if we change our brain, our body or our environment in nontrivial ways, we will change how we experience our world, what things are meaningful to us, and even who we are (Johnson 2007: 1). But for my investigation the question is still there; are the somatic practices one of these nontrivial ways to change the way we think?

Let’s look for an answer from a deeper level. We, for sure, cannot be consciously aware of all complicated and intricate operations in our body. Johnson mentions body images and body schema to distinguish this nonconscious process by cited from Shaun Gallagher: there is a body image which we are aware of, and body schema which functions without awareness. Gallagher states that body image is “a system of perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs pertaining to one’s own body”, and body schema is “a system of sensory motor capacities that function without the necessity of perceptual monitoring”. While body schema makes possible our perception, bodily movement, and kinesthetic sensibility, it hides all these operations from our view. “Body schema involves a set of tacit performances that play a dynamic role in governing posture and movement (Johnson 2007: 5)”. As Johnson states, “there is a continuity of process between these immanent meanings and our reflective understanding and employment of them” (Johnson 2007: 25). So, according to Johnson, our most abstract concepts such as justice, mind knowledge, truth and democracy are based on aspects of our sensory motor experience, even though they don’t seem to be (Johnson 2007: 273).

There is a similar operation about feelings, too. Here I will follow Antonio Damasio’s arguments, which make very clear the connection between feelings and body images. According to Antonio Damasio, “a feeling is the perception of certain state of the body along with the perception of certain mode of thinking and thoughts with certain themes” (Damasio 2003: 90). It simply means that feeling is the idea of the body being in a certain way (Damasio 2003: 87). This argument highlights the connection between feelings and the body images. Damasio indicates that the body produces two types of body images: “images from the flesh, which comprises from body’s interior images of neural patterns of visceral (e.g. pain, nausea...) and images from special sensory probes, which are based on the state of activity in particular body parts when they are interacting with something from the environment” (Damasio 2003: 196). According to him we need these two types of images to perceive objects and events, and also to respond to them. These images are mapped by neuronal ways in the specific brain regions and we perceive that as feelings. This is also the source of what we experience as thoughts. So to speak, perceptions of feelings occur in the brain’s body maps which are related to internal and external body images.

If we go back to some of somatic practices’ promises, we’ll see that some practices already have such scientific roots. For example, in The Feldenkrais Method participants perform small-ranged movements in softly, and in easily to identify and differentiate muscular contraction that would promote a feeling of ease of movement accomplishment. In that way, as Batson states, habitual movement patterns buried in the body schema can be disturbed and changed. As the old habitual patterns begin to dissolve in an environment of ease and safety, new options for coordination become possible. Occasionally, “imagery is used as a foundation for body scanning and augmenting the body image” (Batson 2009). So, if we accept Damasio’s and Johnson’s arguments, we have valid foundations to believe that we can alter our movement choices, our relations with our environment, and our imaginative and transformative ways of thinking by working on our own body images and our bad bodily habits.

The Basis of The Commedia School Curriculum as an Example of Somatic Approach in Theatre Education

When I advocate somatic education not only in actor training but also in director training, I don’t mean just some classes based on somatic practices. Rather, I urge a curriculum intertwine with somatic approach. Such a curriculum is created with understanding of “being” as not separated between physical and physiological but as “wholeness”. Beside its personal benefits on the students, somatic approach in theatre education also offers “a path” to work in the creation process. The path which requires putting individuals at forefront of a technique (or it’s better to say: putting individuals before teaching a technique).

The Commedia School was founded by Ole Brekke and Carlo Mazzone in Copenhagen in 1978. It is a theatre school which aims to train students not just as actors but also as independent artists, who can create their own opportunities and productions and help to broaden theatre ecology. The school’s curriculum is based on the pedagogical methods of Ole Brekke, Carlo Mazzone-Clementi, Jacques Lecoq, and Moshe Feldenkrais. I won’t mention the part of Lecoq pedagogy in the curriculum but I’m going to try to explain which aspect of the pedagogy makes it to get closer to the somatics. Ole Brekke, who had worked as a coordinator of the school from 1978 to 2018, is the one who mostly brings the somatic quality to the whole training process. He has a background in dancing, somatic practice in Feldenkrais method and yoga as well as in acting, directing and teaching. So it won’t be wrong if I claim that his bodily experiences and knowledge account for his theatre philosophy as a teacher and as a director.

Figure 1: Ole Brekke and Carlo Mazzone-Clementi in 90s

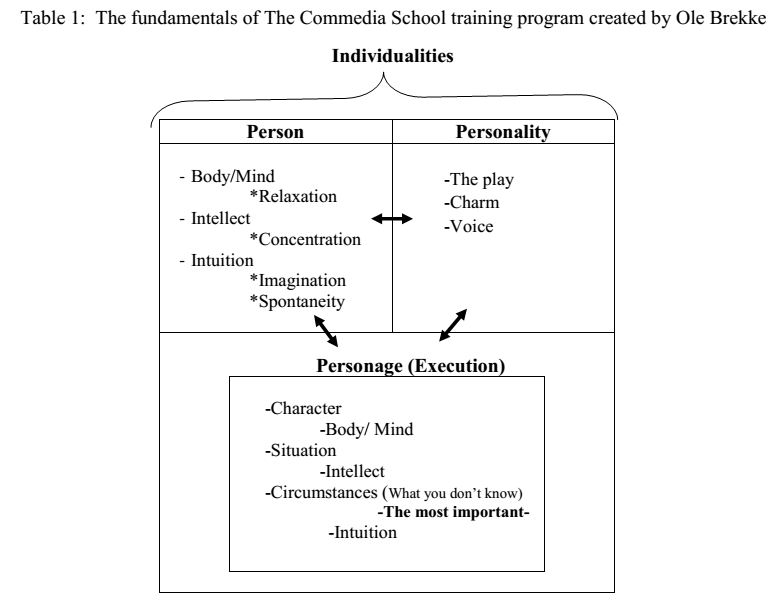

Why I describe his teaching and directing philosophy as a somatic training/approach, even if he doesn’t have such a claim is that he emphasizes foremost the student’s/actor’s individualities during training or rehearsals. He describes his (and also Carlo Mazzone’s) approach as more pre-Lecoq. He starts training processes focusing on basic, fundamental things such as searching for relaxation, concentration, imagination as well as serving your partner, surprising yourself, spontaneity, being lost. During the training, the student’s individualities are at the forefront of the process. As you can see in the chart, the school curriculum is founded on three main baselines which are interwoven: Person, personality and personage (see table 1).

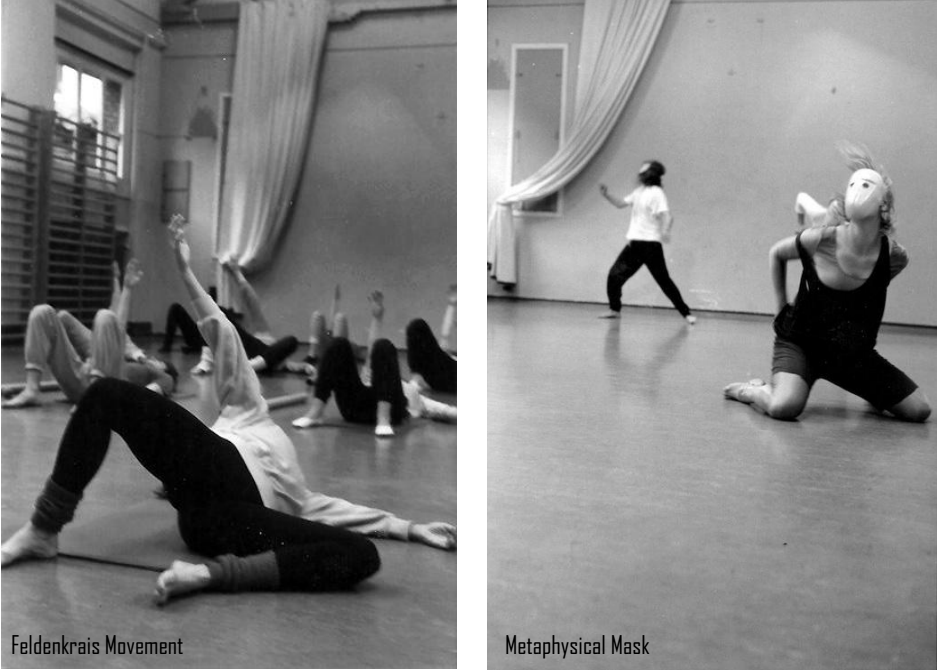

The Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement exercises are utilized to heighten one’s sense of awareness, awareness of our own body and awareness of our surroundings. As we do the small-ranged movement softly and easily, we concentrate our own body and inner experience. As we are doing these exercises, the tension is released. These relaxation and concentration put the body in a condition ready to play and to respond. It triggers imagination and promotes spontaneity. This is the condition that we have to look for on the stage or even in the rehearsals. Our voice becomes richer and more voluminous; we become more playful and charming on the stage as performers. So relaxation, concentration and imagination are the preconditions in preparation for the creation process. If these are accomplished, one can execute creative action to access that ability to create.

Feldenkrais exercises are not the only thing that is this training of somatics based on. Ole Brekke uses somatic kind exercises, which I call transition exercises, to help students to be able to reach that condition in the different situation. He called these exercises “shower exercises” and they are process oriented exercises. I want to explain how they work by an example of “the tissue exercise”.

Tissue exercise: A tissue is put on a far corner of the room. One stands away from the tissue in the opposite corner and with eyes closed walks towards the tissue. When at the tissue, she bends and points her finger to the floor where the paper is. Then she opens her eyes to see if she has come close to the paper.

In this very simple exercise, the main goal is not to find the tissue with eyes closed. The main goal is to be aware of which condition we are in. Are we relaxed, concentrated, and imaginative? They are used for the same purpose as Feldenkrais exercises – to invigorate awareness of body and surroundings, right in the here and now. Moreover, they also function to serve as a transition for students and actors to learn how to find that condition that they reached in Feldenkrais exercise. As they are doing the exercise, they are in the different position than the Feldenkrais exercise. They don’t lie down, they are not on their own, there are other people watching them but still they need to do something that looks very easy. They need to find out which condition they are in. They have to relax, concentrate and imagine reaching the tissue, and furthermore, they have to transmit the awareness of Feldenkrais exercise to that situation. This transition exercise is repeated several times, over the training and the rehearsals. Each time as we are doing the exercise, we explore different things about the condition we are in at that particular moment and surroundings. Brekke emphasizes that the search for the desired fundamental state of “being” that includes relaxation, concentration, imagination and execution is the basis for this exercise. Furthermore, this fundamental level is crucial to recognize one’s own authenticity.

Figure 2: Pictures from The Commedia School Training

Here, I would like to emphasize an important point which makes Brekke’s approach valuable. It’s important to use somatic practices as a part of the curriculum, but what’s more important is to design the curriculum by expanding somatic perspective to the whole training process. Besides using Feldenkrais method practices, Brekke creates exercises to be able to transmit that awareness into other situations and circumstances. After that, it becomes easier to employ every kind of technique (in the sense of Lecoq, they are melodrama, masks, Buffoon, etc.). So to speak with Brekke’s words: “All these shower exercises put you in a condition where you can understand, how those things what you develop there, are applied to the other exercises in one specific style” (Personal interview with Ole Brekke, 25. 4. 2018).

When he explains, why these kinds of exercises are important, he cites Lecoq: “The impression is more important than the expression”, and he explains this quote:

As you make a movement then you get an image from the movement that movement suggests or strikes your imagination. It’s the movement that provokes your idea or imagery. That is the image that is authentic, that is the image that will be seen by others as well. It may not be the image that you would like to express. So you have to accept the image you get from the movement because that’s what’s real. So the impression is more important than the expression. The impression you get from your movement is more important than your desire to express something. It is authentic. What you have to do as a movement trained person is to find the movement that will give you the impression which is equal to that expression that you would like to make. Especially in the creation process, you have to have that awareness of yourself (Personal interview with Ole Brekke, 25. 4. 2018).

Conclusion

Although somatic movement education is getting widespread in theatre education day by day, there are still “conceptual divisions of psychological and physical approaches to actor training” (Kemp 2010). And somatic education still is considered mostly as a part of the actor training; not for the other participants of the theatre making process. Through using somatic practices in director training it’s possible “to create process over goal-oriented product by enhancing kinesthetic awareness in a nonjudgmental and non-competitive environment, to use sensory awareness to modulate movement range and effort to uncover the potential for new mobility, to have resting phases in which the participant is given time to listen to the body, to clarify what sensations have arrived and differentiate wanted from unwanted stimuli, and to consolidate motor learning” (Batson 2009). And also, somatic practices make possible to be a good observer of others’ movement.

Somatic knowledge is not something that one can comprehend just intellectually without doing. So, directors have to experience somatic knowledge, as actors do, in search for authenticity and precision. In the era of working with/on/to bodies (Lehmann 2006), the director can facilitate each performer to a fundamental level of readiness to create and to improvise using actor’s own uniqueness through the somatic practices. In this way, a director can be able to make an actor a co-creator of the performance. So, somatic practices can be used as a way of initiating a sensible environment for creation.

If we consider somatics as a call to understand the body in a holistic way and to go back to bodily experience and awareness, somatic education can be the way to reconsider the purview of aesthetics. Aesthetic is not just “a subjective dimension of human life” (Johnson 2007: 3). As Johnson indicates, “it must become the basis of any deep understanding of meaning and thought”. In this sense, he highlights the embodied aspect of aesthetic as he claims meanings and thoughts are embodied. I posit that somatic theatre education may provide students new aspects of “aesthetic” via focusing on their own bodily experience and awareness. Only in this way, as Johnson indicates, we can go beyond “consummated meaning” of aesthetics, and it may become an investigation of what is meaningful for us.

Works Cited